|

The Box Formation

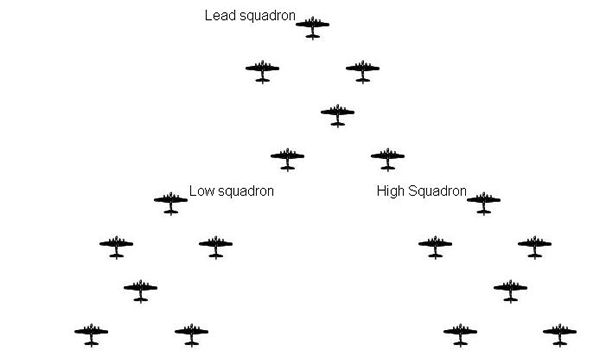

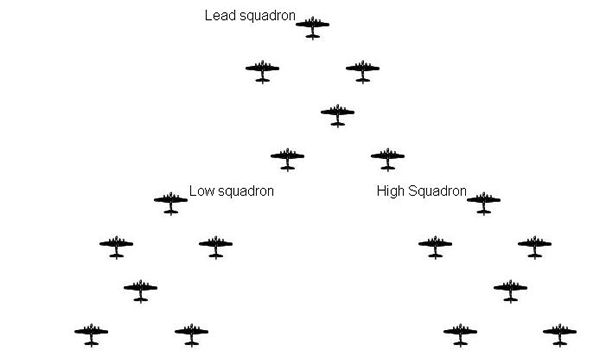

At first, American heavy bombers flew in combat boxes of 18 aircraft

with succeeding boxes following 1.5 miles (2.41 km) behind. To improve

the defensive formation, this was replaced by the wing formation that

combined three 18-plane groups. Also, instead of flying behind each other,

the groups were positioned at high, medium and low level. The medium altitude

group would fly slight ahead in the lead with the high squadron above

and to the right with the low squadron beneath and on the left. The resulting

54 plane formation occupied a stretch of sky 600 yards long (549 m), a

mile (1.61 km) or so wide and half a mile deep (.80 km). Other wings might

fly identical formations to the target at six-mile (9.65 km) intervals.

This is the typical formation of 18 aircraft in a single squadron in

a bomber stream. Bomber raids started as small intimate affairs. Usually

moderate altitudes with a modest number of bombers, striking simple targets

along the coast. As the numbers of available bombers increased the raids

became larger and more daring. Some of the largest raids employed 1000

bombers to strike targets in Germany. This bomber stream could be as long

as 100 miles (161 km) and as wide as 1 mile (1.61 km). At 180 mph (290

km/h) over the target an air raid could last from 35-45 minutes.

Each squadron in the bomber stream was composed of 3 flights of 6 aircraft

each. Each flight had two elements of 3 aircraft each. In this formation

the lead flight flew at the designated altitude. The planes in an element

were separtated by 50' (15.2 m) horizontally, and each element was also

separated by 50' (15.2 m). The high flight was 50' (15.2 m) behind and

50' (15.2 m) right of the lead flight. The low flight was 50' (15.2 m)

behind and 50' (15.2 m) left of the lead flight.

This deployment of aircraft made it nearly impossible for a single fighter

to get hits on multiple aircraft in a single pass through a squadron.

Secondly, it also spread the attacking force out making it difficult for

it to concentrate its fire. Thirdly, this opened up the gunners field

of fire increasing their effectiveness.

Attacking A Flying Fortress

To reliably destroy a B-17, the attacker had to either break

the integrity of the flight deck or explode the bombs in the bomb bay.

Anything less only damaged the bomber. Hits on less vulnerable areas like

the massive vertical stabilizer and rudder might cause the aircraft to

slow but it would struggle on. Consolidated B-24 Liberator’s had

a tendency to explode when hit but the B-17 rarely did.

Attacking a formation of American bombers from the rear was foolhardy

due to the coverging fire from the bomber’s tail and ball turret

gunners. Tail attacks also exposed the fighter pilot to additional fire

due to the reduced closure speed. The standard fighter approach from 1000

yards (914.4 m) astern with an overtaking speed of 100 mph (161 km/h)

took over 18 seconds to close the distance down to 100 yards (91.4 m).

Initially, head-on attacks were conducted with a flat angle of attack

but this made judging the range to the target very difficult. German pilots

were initially intimidated by the Fortress’ 104 ft (32 m) wingspan.

The urge to open fire from too far away and to breakaway too soon for

fear of collision looming large in the gunsight was overwhelming. Further

refinement of the tactic showed that the optimum angle of attack when

approaching from head-on was from ten degrees above the horizontal, what

American bombers crew’s came to call "12 O’clock High."

This greatly simplified the problem of estimating range and permitted

a constant angle of fire similar to ground strafing.

When intercepting a bomber force, German fighter units initially flew

a parallel course off to one side outside the range of the defensive guns.

After reaching a point about 3 miles (5 km) ahead, either three or four

plane groups peeled off and swung 180 degrees around to attack head-on

in rapid succession. It was critical for the fighters to maintain some

semblance of cohesion, or at least visual contact, so after each pass

they could regroup for repeated concentrated attacks. That was the theory

anyway. In reality, many pilots ended the first pass with a split-S manoeuver,

inverting and diving down and away from the defensive fire above them.

With increased experience, German fighters began to make their head-on

attacks using either in line astern or with the entire unit spread out

abreast in the "company front" formation. The recommended procedure

was to pull up and over the bombers and then from their position of advantage

above, the German fighters were quickly able to launch another attack.

It was critical for the fighters to maintain some semblance of cohesion,

or at least visual contact, so after each pass they could regroup for

repeated concentrated attacks. That was the theory anyway. The huge tail

fin of the Fortress posed a collision risk and many German pilots preferred

to break away below. Either they dipped the noses of their aircraft and

passed close underneath, or rolled inverted and broke hard down with the

"Abschwung" (Split-S maneuver.) This took them well below the

bombers and valuable minutes were lost before they could gain sufficient

height to attack again.

Attacks from above had the advantage of placing the vulnerable oil tanks

(inside of the inboard engine nacelles) and wing fuel tanks (inside the

outboard engine nacelles) directly in the attacker’s path.

By the summer of 1943, the Germans had deployed the Focke Wulf FW 190A4,

a dedicated bomber killer armed with two 7.9mm machine guns and four 20mm

cannons. With all guns functioning, a three-second burst fired about 130

rounds of ammunition. The Luftwaffe estimated that it took an average

of 20 hits from the 20mm cannon to destroy a B-17. Analysis of gun camera

film revealed that the average German pilot scored hits with only 2 percent

of the rounds fired, thus on average, 1000 rounds were fired to score

the 20 hits required.

Seeking to stem the armada of Allied bombers, the Germans tried dropping

pre-set bombs on them timed to explode when they were at the same height

as the stream. The Germans also employed 210mm, tube-launched, spin-stabilized

rockets employing 248-pound (113 kg) projectiles with 80-pound (36.3 kg)

warheads (a version of the German Army’s "Nebelwerfer").

The warheads were time fused to detonate at between 600 to 1200 yds (549-1097

m) from the launch point. To inflict damage the rocket need only explode

within 50 ft (15.2 m) of the target although the warhead would also detonate

if it struck a bomber. Often an exploding B17 caused enough damage to

adjacent planes to bring down another or even two. Although not particularly

accurate, the rockets served well to break up the formation. The added

weight and increased drag of the installation severely degraded the performance

of the German fighters and made them vulnerable to Allied fighter escorts.

With the advent of American long-range fighters, the Germans were forced

to change tactics again. The need to inflict damage on the bombers was

ever increasing and to accomplish this their planes needed additional

and heavier armament. The weight of these additions decreased the performance

of their fighters such as to make them easy victims if Allied Fighters

were encountered. The Luftwaffe's answer was the "Gefechtsverband’

(battle formation) consisting a "Sturmgruppe" of heavily armoured

and armed FW-190A8’s escorted by two "Begleitgruppen" of

light fighters, often Bf 109G’s. The task of the light fighters was

to engage the escort while the heavy fighters attacked the bombers. It

was a great theory but difficult to employ. The massive German formations

were unwieldy and took time to assemble. They were often intercepted by

Allied Fighters and broken up before they reached the bombers but when

they did make it through the results could be devastating. With their

engines and cockpits heavily armoured, the Sturmgruppen pilots braved

the storm of fire and attacked from astern.

Later in the war, the Germans introduced the Mk 108 30mm heavy cannon

capable of firing 600 11-ounce (330 gram) high explosive rounds per minute.

Three hits with this weapon were usually sufficient to bring down a Flying

Fortress. On the other hand it was a low velocity weapon and its effective

range was shorter than the 20-mm cannon forcing German pilots to fly even

closer to get hits.

The jet propelled Me 262 introduced in the last year of the war was 100

mph (161 km/h) faster than contemporary piston-engine fighters and well

armed with four 30mm cannons. In a head-on attack, its 350 yards (320

m) per second closing rate was too fast to allow accurate aiming or to

allow optimum use of its short-ranged armament. To overcome this, German

Jet pilots used the "roller coaster" attack. Approaching from

astern at about 6000 ft (1,829 m) above the bombers, the jets pushed over

into a shallow dive starting about 3 miles (5 km) away. They quickly built

up speed such that the escorts could not follow them. Diving down until

they were about a mile (1.61 km) behind and 1500 ft (457.2 m) below, they

pulled up sharply to bleed off speed, leveling off at 1000 yds (914.4

m) astern in position to deliver an attack.

Desperate to inflict massive losses on the American Bomber stream and

force a month long bombing pause, the Germans concocted a plan for a massive

ramming attack. Late in 1944, Oberst Hans-Joachim Herrman proposed using

800 or so high altitude Bf-109G’s stripped of armour and armament

to reduce weight for such an attack. Lightened in this manner, he calculated

the planes could reach 36,000 ft (10,973 m) well above the American escort

fighter’s ceiling. German pilot losses were predicted to be around

300, more or less what was lost in a normal month’s fighting. Aircraft

losses would be much higher of course, but by this point numbers of aircraft

were not the Luftwaffe’s problem. Trained pilots and especially fuel

were. Fully trained fighter pilots were too valuable to be wasted in these

attacks, so volunteers were called for from the training units. The first

ramming unit, "Sonderkommando Elbe" formed in April 1945, flew

a single mission with 120 aircraft. Its inadequately trained pilots were

unable to inflict much damage. Fifteen bombers were rammed but only 8

were destroyed.

"Fips" Phillips, a 200+ Eastern Front Ace wrote the following

while in command of JG 1 defending against American Bombers over Northern

Germany:

"Against 20 Russians trying to shoot you down or even 20 Spitfires,

it can be exciting, even fun. But curve in towards 40 fortresses and all

your past sins flash before your eyes."

|

Back |

If you came to this page from a search engine click below to access the rest of the site

HOME

|